Bottle and Wine Glass on Table, 1912

© 2018 Estate of Pablo Picasso / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

Spanish wine—such was its allure—it was a muse of Pablo Picasso. According to Tim (aka Timmer) Brown, wine blogger and founder of Catalunya Wine, Picasso’s paintings during his Cubism Period were inspired by the people of the towns and vineyards of the Spanish wine region, Terra Alta, where Picasso lived during his twenties in the mountains.

In October 2004, internationally renowned wine critic, Robert M. Parker, Jr., predicted:

“Spain will be the star. Look for Spain to continue to soar . . . .”

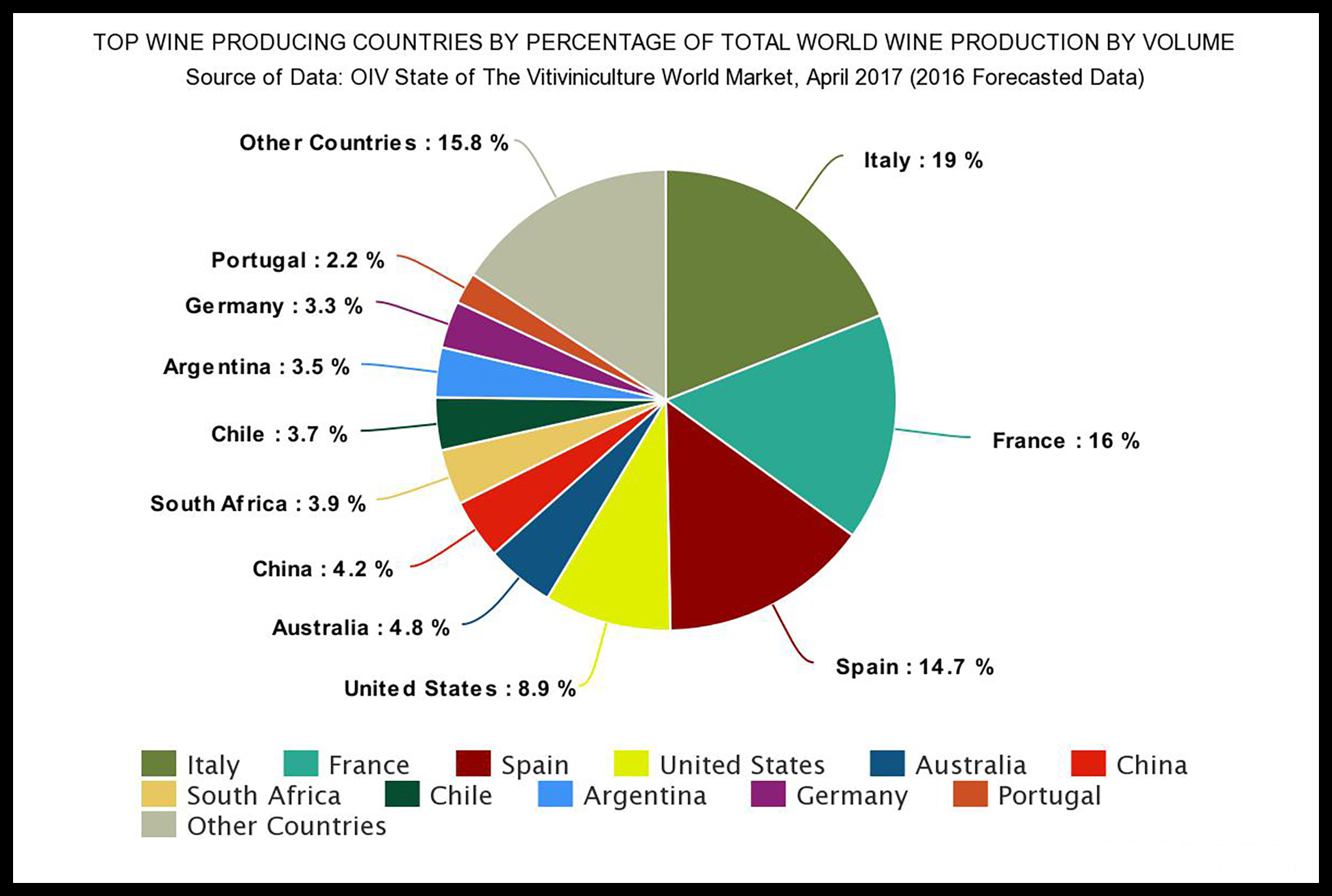

And, indeed, Mr. Parker was correct. Today, Spain is consistently among the top three wine producing countries in the world, along with France and Italy, which combined account for approximately 50% of the total wine production in the world.

Once a great artist’s muse and now a star on the world’s winemaking stage—what makes Spanish wine special?

Once a great artist’s muse and now a star on the world’s winemaking stage—what makes Spanish wine special?

A Story of Resilience, Passion and Dedication

Part of what makes Spanish wine special is its story. The history of Spanish winemaking is a long and interesting one steeped in nothing less than resilience, passion and dedication from which Spain has emerged a leader in the world market, producing striking wines that reflect tradition as well as innovation.

History to Columbus

Phoenicians. The Phoenicians established the city of Gadir (modern-day Cádiz) in c. 1100 B.C. There they started making wine and traded it as a commodity, using heavy and fragile clay containers, called amphorae, for transporting the wine. There is also evidence that grape vines had been cultivated in Spain since between 4000 and 3000 B.C.

Terracotta Amphora with Phoenician Inscription, 7th Century B.C.

Metropolitan Museum of Art (Public Domain)

Roman Empire. After the Phoenicians, the Romans, who ruled Spain from c. 200 B.C. until the collapse of the Roman Empire in the 5th century, planted their vines and introduced their winemaking practices to the local people, mostly the Celts and Iberians. The Celts and Iberians embraced these new winemaking practices, which included fermentation in stone troughs and the use of more resilient amphorae. There is also evidence that wine during this period (although most of it was of poor quality and cheap) was being exported from Spain to Rome, France and England.

Terracotta Amphora

Roman Period, 1st Century A.D.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Moorish Invasion. The Islamic Moors of Northern Africa occupied Spain from the 8th century until their defeat in 1492. The Moors did not drink alcohol, but they also did not impose their beliefs on their Spanish subjects. So while innovation in winemaking was stagnated during this period, winemaking did continue. By the middle of the 13th century, wine was being shipped regularly from Bilbao to England. The quality of the wines varied, from poor and highly alcoholic with no other redeeming qualities, to very good wines that competed with French and German wines.

Foundations of Modern Winemaking

Rioja Transforms. Following the final defeat of the Moors in 1492, Spain emerged a united country. It was shortly thereafter that Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the West Indies revealed a new world of trade for Spain. But it wasn’t until the middle of the 19th century that the foundations of modern Spanish winemaking were established by two men who brought Bordeaux winemaking technology to the Rioja wine region and transformed it. These men were Luciano de Murrieta García-Lemon (the Marqués de Murrieta) and Don Camilo Hurtado de Amézaga (the Marqués de Riscal).

Camilo Hurtado Amézaga

El Marqués de Riscal, 1888

By Original Unknown. Computerization FCA00000 (La Ilustración Española y Americana. 1888.) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

Each of Murrieta and Riscal, while exiled from Spain, spent time studying in Bordeaux and believed that the wines of Rioja could compete qualitatively with those of Bordeaux—with the proper treatment. A radical and expensive proposition for Spanish winemakers, who at the time, were still utilizing the Roman methods of winemaking.

In spite of the resistance they encountered, the men succeeded in bringing Bordeaux technology to Rioja. Murrieta returned to Rioja in 1850, and in a borrowed bodega made his first vintage in 1852. Riscal planted a vineyard in Elciego and founded a bodega in 1860. Murrieta later founded his own bodega, the Ygay estate, outside of Logroño in 1872.

Wine Bottles in Cave

Bodegas Marqués de Murrieta

By Darrin Jenkins/alamy.com

Murrieta and Riscal were immensely profitable in their ventures. The Bordeaux technology proved its value, and eventually most of the other Rioja winemakers followed suit.

Marqués de Riscal Hotel, Rioja 2016

Vega Sicilia. It was around this time that the seeds of progress were planted in nearby Ribera del Duero by entrepreneur Eloy Lecanda who inherited the estate we know today as the iconic Vega Sicilia and began to professionally make wine in 1864. Having also spent time in Bordeaux, he brought back to the area French oak casks, winemaking skills and grape varieties, which grew successfully alongside the native Tempranillo (known there as Tinta del País).

Stainless Steel. The next significant development in Spanish winemaking came about 100 years later with winemaker Miguel Torres, who introduced stainless steel winemaking to the Catalonia wine region. Stainless steel allowed winemakers to control fermentation temperatures with ultra precision, and in turn, improve wine quality.

Bodegas Vivanco, Rioja 2016

Inspired by the stainless steel winemaking kits he saw in France and Australia in the 1950s, Torres installed his own tanks at his winery in Catalonia in the 1960s. Torres’ new undertaking flourished, causing most winemakers throughout Spain to subsequently follow in his footsteps.

A Dark Period

Despite such pioneering achievements, most of the 20th century in Spain was wrought with setbacks and turmoil that not only affected the country as a whole but also its winemaking industry.

Phylloxera, a pest which had devastated the vineyards of France and other European countries during the 19th century, spread to Spain and took hold of Rioja by 1901. Although by that time a remedy had been developed, vineyards throughout the country still had to be replanted and many traditional, indigenous grape varieties were facing extinction.

Political infighting further stifled the country. The monarch, Alfonso XIII, was abdicated and the Second Republic was proclaimed in 1931. Soon thereafter Spain was embroiled in the horrific and bloody Spanish Civil War (1936-39), which ended in a victory by the right-wing forces of General Francisco Franco. Franco ruled over Spain as a military dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. A dark period for Spanish wine.

Franco’s regime suppressed various economic, personal and religious freedoms. In so far as wine was concerned, he believed that wine should only be used for church sacraments. As wine blogger Tim Brown reveals further in this article on the subject:

“Franco had a significant impact on the industry countrywide, not only in his attitude, but punctuated by his actions when he had the removal of vineyards in the Viura and other regions executed by his forces.”

Spanish Wine’s Resurgence

Spain emerged from the dark period with a vengeance. A significant revival of Spanish winemaking followed the death of Franco. The transition back to democracy and economic freedom promoted growth in the market, including a new interest in high quality wines by the urban middle class.

This revival was augmented when Spain joined the European Union in 1986. Joining the European Union further promoted the movement of ideas and brought investment, better production methods and extensive modernization to Spanish wine regions. Since then, as described in this article of El País Semanal, there have been generations of entrepreneurs reviving vineyards throughout the country, including in unlikely places, such as the Balearic and Canary Islands.

Today, as Robert M. Parker, Jr. predicted in October 2004, Spain is “a leader in wine quality and creativity, combining the finest characteristics of tradition with a modern and progressive winemaking philosophy.”

Bodegas CVNE, Rioja 2016

Wines That Are Unique and Authentic

Spain’s Diverse Regions

Spanish wines are made in a range of styles that reflect the country’s diverse regions and native grape varieties, offering the consumer a unique and authentic experience with each wine.

As described in The Oxford Companion to Wine online by world-renowned wine critic, journalist and Master of Wine, Jancis Robinson:

“The country’s regional diversity is reflected in her wines, which range from light, dry whites in the cool Atlantic region of Galicia to heavy, alcoholic reds in the Levante and the Mediterranean south. Andalucía in the south west is known for the production of fortified and dessert wines, the most famous of which sherry.”

Vineyards Along Sil River, Ribeira Sacra

Lugo (Galicia)

By Noradoa/shutterstock.com

Spain’s Grape Varieties

The uniqueness and authenticity of Spanish wines also stem from their strong regional ties to the native grape varieties used to make them—which are as diverse as Spain’s wine regions. Although winemakers are permitted to grow and sell international varieties (such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Sauvignon Blanc and Chardonnay), Spain’s true claim to fame is its native grape varieties grown in specific regions throughout the country.

Native Black Grape Varieties

Tempranillo. Among the most important native Spanish black grape varieties is Tempranillo, which also goes by various other synonyms (e.g., Tinto del País, Tinta de Toro, Tinto Fino) depending on the region where it is grown. Tempranillo is predominantly grown throughout the vineyards in northern and central Spain, and is the star of the Rioja and Ribera del Duero wine regions.

Tempranillo Grapes, Rioja Alavesa

By María Jesús Tomé

[CC BY 2.0 – https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0]

via Wikimedia Commons

Tempranillo can be made into a wide range of wine styles, from light with relatively little oak aging and vibrant red fruit to more opulent, age-worthy oaked styles with concentrated fruit. While Tempranillo can make up 100% of a wine, it is often blended with small amounts of other native black grape varieties, such as Garnacha, Mazuelo or Graciano, or international varieties, such as Cabernet Sauvignon.

Tempranillo will also have different expressions from region to region. For instance, the subregions of Rioja, Rioja Alta and Rioja Alavesa, which are at higher altitudes and benefit from the cooling influences of the Atlantic Ocean, generally produce wines that are lighter in color, with more finesse and moderate tannins. In contrast, in Ribera del Duero, which is southwest of Rioja, the summers are short, hot and dry, the winters are very cold and the region is cut off by mountains from any maritime influences of the Atlantic Ocean. As a result, Tempranillo in Ribera del Duero has a compressed growing season and reaches higher levels of ripeness, typically resulting in darker colored wines that are more robust and higher in tannins.

Garnacha Vines in Spain

CC0 Public Domain

Garnacha Tinta. Another important native Spanish black grape variety is Garnacha, which is originally from Spain but is known more commonly in France and other areas outside of Spain as Grenache. It is grown particularly in the north and east of Spain, including the regions of Rioja, Navarra, Madrid, La Mancha, Penedès and Priorat, among others. Wines made solely from Garnacha tend to be full bodied, high in alcohol and low in acidity with soft tannins and red fruit flavors. As such, Garnacha is also an important blending partner in the wines of Rioja, where it is blended with Tempranillo, and in Priorat, where it is blended with Cariñena (known as Carignan in English and Mazuelo in Rioja). It is also used for making rosado, Spanish rosé wine.

Monastrell. Although not as well-known as Tempranillo or Garnacha, Monstrell (known in France as Mourvèdre) is another significant native Spanish black grape variety. It is grown in south eastern Spain, where the climate is hot and dry and the growing seasons are long (e.g., Jumilla, Yecla and Alicante), yielding intensely colored wines that are high in tannins and exhibit black fruit flavors, spices and leather.

Others. Other native Spanish black grape varieties include Graciano, Cariñena (or Mazuelo in Rioja) and Mencia.

Native White Grape Varieties

Albariño Grapes on a Vine

By Avarand/shutterstock.com

Albariño. Among the important native Spanish white grape varieties is Albariño. It is grown in the northwest of Spain in Galicia, which is comprised of several wine regions, including the well-known Rías Baixas region. The climate of Galicia is damp and relatively cooler than most other wine regions of Spain. As such, wines made from Albariño, which is naturally high in acidity, are typically light, fresh and fruity without any oak influence (although, it is also made in richer, fuller bodied styles). The wines are generally a pale, golden lemon color with moderate alcohol and very aromatic, with flavors of citrus and stone fruit, such as white peaches and apricots.

Verdejo. Another key native Spanish white grape variety is Verdejo, the signature wine of the Rueda region in Castilla y León, which sits in between Ribera del Duero and Toro. A typical wine made from Verdejo is a pale yellow color with hints of green, light bodied with fresh acidity, with notes of grass, citrus and stone fruit, such as peaches. It is similar in style to Sauvignon Blanc with which it is often blended to make an aromatic, fuller bodied wine.

Others. Other native Spanish white grape varieties include Airén, Godello, Viura (known as Macabeo in Cataluña), and Palomino.

Wines of Exceptional Craftsmanship and Value

Spanish wines in general, particularly in the United States, are sold for prices far less than they ought to command for their quality, offering the consumer exceptional values. As so succinctly put in this article of Food and Wine:

“Want value plus incredible craftsmanship? Go to Spain. There’s no other country on earth making as many amazing under-$20 bottles.”

However, this phenomenon is not limited to wines under $20. It also occurs with higher end and premium Spanish wines, which will typically cost a fraction of what equivalent wines from France or Italy would cost.

This disconnect between quality and price appears to be largely due to problems with branding and marketing. As described by Ian Mount in this article of Fortune, France and Italy have simply done a better job than Spain in branding and marketing their wines. A sentiment we’ve heard echoed many times by sommeliers and winemakers throughout our travels in Spain.

While industry experts have differing opinions on how to solve the problems, they seem to fundamentally agree that excellent quality alone does not sell wine. As Mount writes, they’re searching “for the best way to tell their wine’s story in a way that grabs the luxury consumer in what is a very crowded market.”

Bottles of Wine (Valbuena de Duero), Vega Sicilia Winery

By James Struck/alamy.com

Pablo Álvarez, who runs the renowned Vega Sicilia winery in Ribera del Duero, believes that travel is an important means of promotion. In the June 30, 2016 issue of Wine Spectator, in the article entitled “The Man Behind Vega Sicilia”, Álvarez says, “I think the big problem of Spain is—I don’t know why this is—the Spanish don’t like to travel. It’s something in our mentality.”

A notable exception to this, Álvarez, an avid, worldwide traveler, also tells the magazine that when he travels “all the good sommeliers are French and Italian”, who in turn, serve and promote French and Italian wines. Ultimately he says, “Spain is on the right track, but something has to change.” “It is necessary that we move.”

Yet, despite such problems, Spain has achieved great success with its wines—undeniably, the product of the country’s resilience, passion and dedication, and a testament to the uniqueness, authenticity, exceptional craftsmanship and value of its wines.

Other Sources:

John Radford, The New Spain, A Complete Guide to Contemporary Spanish Wine (London: Mitchell Beazley, 2004), 9-20.

Jancis Robinson, The Oxford Companion to Wine (New York: Oxford University Press, 2015), 693-697.